On an inconspicuous street corner in the Gonzalez-Suarez sector of Quito, you can sometimes find Maria Ugsha selling the traditional masks made by her husband, Juan Manuel, an artist from Pujilí. From a distance, it is impossible to see the skill used to make each mask. But once up close, it is easy to tell the difference between these and many of the lesser quality masks sold at tourist shops around the Mariscal. In fact, most of these masks could compete with any sold at the high-end Olga Fisch boutique.

On an inconspicuous street corner in the Gonzalez-Suarez sector of Quito, you can sometimes find Maria Ugsha selling the traditional masks made by her husband, Juan Manuel, an artist from Pujilí. From a distance, it is impossible to see the skill used to make each mask. But once up close, it is easy to tell the difference between these and many of the lesser quality masks sold at tourist shops around the Mariscal. In fact, most of these masks could compete with any sold at the high-end Olga Fisch boutique.

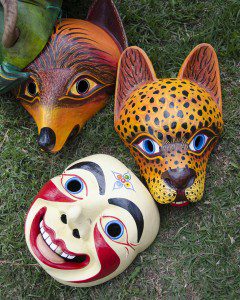

Several deserve mention. There are the smiling, black-faced Mama Negras, a character that blends traditions of the Spanish Colonists with indigenous Ecuadorian mythology. She is at once the Virgin Mary and the Pachamama, the mother earth figure sacred to all Quichua. She is celebrated at an annual festival in nearby Latacunga.

There are grinning white-faced masks, seemingly the opposite of Mama Negra. These are the shaman that cleanse the spirit and accompany Mama Negra on parade. They look almost like clowns set on evil intentions, their smiles failing to hide a malevolence that seems carved into their very faces.

Then there are the devils, most in various shades of greens with yellows or oranges with browns, some with teeth that look as if they were pulled straight from an ogre’s mouth, some with curved horns whose first owners must have been some of the sheep that live on the mountainside farms of Pujilí. These evil creatures should be hideous to look at but somehow they make me think of Dionysus, the Greek god of fertility and of wine. They are out to make trouble but not necessarily commit acts of true evil.

Then there are the devils, most in various shades of greens with yellows or oranges with browns, some with teeth that look as if they were pulled straight from an ogre’s mouth, some with curved horns whose first owners must have been some of the sheep that live on the mountainside farms of Pujilí. These evil creatures should be hideous to look at but somehow they make me think of Dionysus, the Greek god of fertility and of wine. They are out to make trouble but not necessarily commit acts of true evil.

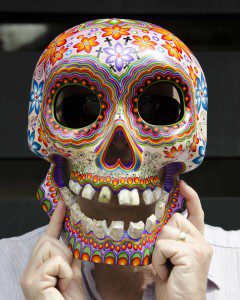

María could tell we were very interested in the selection on offer. She quietly moved to a shaded corner, pulled out a large plastic bag, reached inside and carefully removed the mask that soon became ours.  It was a large skull, slightly larger than a man’s head, with huge openings for the eye sockets and non-existent nose and a grinning mouth, full of crooked teeth. I immediately noticed the single golden tooth wink at me. Then my eyes wandered across the surface. This skull was highly decorated with repeated flower motifs in oranges and purples and blues and blacks. Small crosses encircled a single flower on his forehead. His eye-sockets were ringed with bright colors that almost made me dizzy. His entire face danced with color. He would make a perfect reminder of the upcoming celebrations for Día de los Difuntos, or Day of the Deceased, on November 2nd.

It was a large skull, slightly larger than a man’s head, with huge openings for the eye sockets and non-existent nose and a grinning mouth, full of crooked teeth. I immediately noticed the single golden tooth wink at me. Then my eyes wandered across the surface. This skull was highly decorated with repeated flower motifs in oranges and purples and blues and blacks. Small crosses encircled a single flower on his forehead. His eye-sockets were ringed with bright colors that almost made me dizzy. His entire face danced with color. He would make a perfect reminder of the upcoming celebrations for Día de los Difuntos, or Day of the Deceased, on November 2nd.

Each of these masks is meticulously hand carved from pine and then painted with several layers of brightly colored acrylics. The devil is in the details and these masks have them, whether it is a finely touched feather on the face of a bird or the repeated symmetrical flower motif on the Día de los Difuntos Skull. Juan Manuel has obviously been perfecting his art for more than 30 years.

Each of these masks is meticulously hand carved from pine and then painted with several layers of brightly colored acrylics. The devil is in the details and these masks have them, whether it is a finely touched feather on the face of a bird or the repeated symmetrical flower motif on the Día de los Difuntos Skull. Juan Manuel has obviously been perfecting his art for more than 30 years.

María can usually be found on sunny Fridays, Saturdays, and Sundays between the hours of 9am and 5pm. She does not open for business in rain or heavy fog. Smallest masks range upward of $7 and the largest should cost about $75. She is willing to give a small discount on multiple purchases but she obviously knows the value of her husband’s work and drives a hard bargain.

If you would like to call the workshop in Pujilí to special order an item or to request a visit, Juan Manuel’s cellphone number is 099-598-6054.

[ready_google_map id=’49’]

0 comentarios